« Le Monde » editorial : Rejecting the National Front

« Le Monde » editorial : Rejecting the National Front

Par Jérôme Fenoglio (Director of "Le Monde")

Far-right National Front leader Marine Le Pen’s advance to the second round of the French presidential elections, and the stinging defeats of both the centre-right Les Républicains party and the centre-left Socialists, pose a new threat to France.

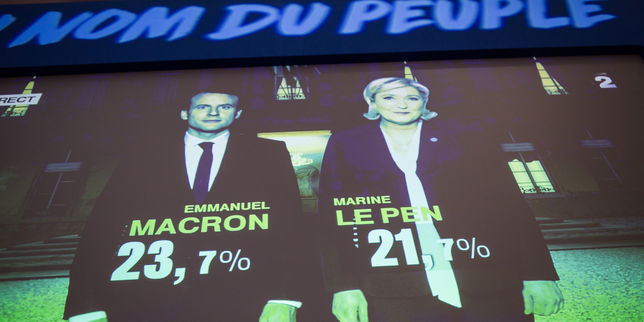

EDITORIAL. The political upheaval seen in the first round of France’s presidential elections was long predicted, but it nonetheless marked radical and surprising changes for French politics. Polls consistently showed that Le Pen would make it to the second round on May 7. In fact, for more than two years France’s political life has revolved around the certainty that the National Front would occupy one of the two coveted places in the final round of voting.

But the phenomenon of Emmanuel Macron and his En Marche! movement is a relatively recent development, and has grown out of the many political dramas leading up to this decisive moment. As a candidate he was able to capitalise on these events and voter discontents with aplomb.

So in the end everything went according to plan, despite the National Front’s weak campaign and its poor showing compared to the highs it has seen in local elections since 2012. And yet it is imperative not to trivialize what the results of the first round mean for France and the gravity of the injury they have inflicted upon the nation: for the first time ever, the National Front (FN) garnered more than 20 percent of votes in a presidential election. Le Pen set a new record for the number of FN voters with 7.6 million – 2.8 million more than her father, FN party founder Jean-Marie Le Pen, won in his surprise advance to the second round to challenge Jacques Chirac in 2002. For the second time in 15 years, a nationalist and xenophobic party – led by a cynical and profiteering family clan – has qualified to compete in the final competition of the French political system.

A forceful rejection of the FN

This recurrence should both serve as a warning to the French of the precarious state of our democracy and trigger a forceful rejection of the FN, much like what we saw in 2002. For Le Monde, this response must be unambiguous. As we reiterated before the election, the National Front party is incompatible with our values, our history and our identity. For these reasons we must hope for Le Pen’s defeat and call on French voters to support Emmanuel Macron.

But the very worst scenario – and the most dangerous and irresponsible one for the future of France – would be to assume that an eventual Macron victory was a certitude. A cursory comparison should suffice to underscore the uncertainty of any such a prediction: Macron enters the final stretch with the support of 62 percent of likely voters (according to an Ipsos Sopra-Steria poll) compared to the 82.2 percent who supported Chirac against Jean-Marie Le Pen in 2002. Twenty percentage points have thus evaporated in just 15 years – as have the calls for demonstrations and the moves to form an anti-FN “Republican Front” seen in 2002.

The challenge for those seeking to disrupt the system is that they are then forced to operate in an environment where nothing remains stable. Macron’s indomitable ascent has caused untold damage to France’s political establishment. Neither of the two main political parties – not the ruling Socialists nor the opposition Les Républicains – managed to make it to the second round. The Socialist Party’s popularity rating has fallen to its lowest level in a half-century. Les Républicains, on the other hand, failed to see that candidate François Fillon, who was thoroughly morally discredited (by a nepotism scandal over fake jobs), was unlikely to triumph politically.

Overcoming anger

The magnitude of these disappointments has inevitably given rise to a great deal of rancor and bitterness. Hamon managed to overcome them quickly enough to make an election night appeal for voters to back Macron.

But on the right, the turn of events seemed a bit harder to swallow. Several prominent conservatives as well as editorialists are pretending to believe that the final outcome is now certain, merely to avoid offering a clear exhortation. Many conservative voters will undoubtedly have a hard time in overcoming their anger, egged on by Fillon, who did not hesitate in blaming conspiracies, the media and the justice system for his troubles.

Macron will also have to take into account the significant percentage (19.6 percent) who cast a social protest vote by rallying behind far-left firebrand Jean-Luc Mélenchon. Defying the longtime practise of French leftists, Mélenchon declined last night to call on his supporters to rally around Macron against the National Front.

And there is no doubt that a significant number of his voters will be tempted to take a similarly ambivalent view of the second round. To convince them to change their minds, centrist Macron must not make the same mistake made by Hillary Clinton, who failed to appeal to many of the leftist voters who supported Bernie Sanders. Remember that just two weeks before the US election, the Democratic candidate was seen as the certain victor in the contest against Donald Trump.

The risk of mass voter abstention – given that the second round falls on the Sunday of a long weekend – is also significant. Macron has less than 15 days to prove to all these reluctant voters that he has taken the measure of the shock suffered by the French political system.